- All matter -- everything that has weight and takes up space -- is made up of particles called atoms. . .

- Matter that can't be broken down into simpler substances is a chemical element, of which there are 88 that occur in nature. An element consists of only one type of atom.

- Atoms can form several types of chemical bonds with each other.

- A group of two or more atoms bonded together is a molecule, and any substance or material that's made up of atoms bonded together is a compound.

- A very common situation: One type of simple molecule, or a group of simple molecules, are strung together in a chain or branched chain.

- Think of a train. There may be only a few types of cars (locomotive, boxcar, tank car, refrigerated car, flatcar, sleeper, diner, caboose. . . ). But by arranging these in different orders, you can make trains of almost any length that will carry virtuallly anything.

- A complex molecule made up of simpler units is a polymer. . .

- and the simpler subunits are known as monomers. When monomers join together to form a polymer, we say that they polymerize.

- Polymers are very common in biology -- proteins, starches, cellulose, chitin, and nucleic acids are all natural polymers. Outside of biology, plastics and synthetic fibers such as nylon are polymers.

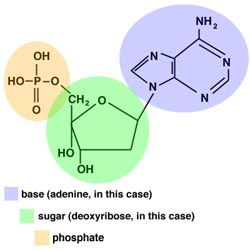

- DNA is a polymer made up of many smaller monomers

called nucleotides. Each nucleotide has three parts: a sugar, a

phosphate group, and a single-ring or double-ring molecule containing

carbon and nitrogen, known as the base.

A typical nucleotide, with adenine as the base - DNA is made up of four types of nucleotides, each with a different base.

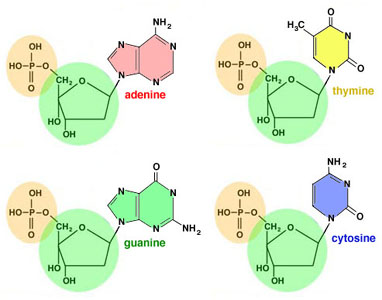

They are: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine,

abbreviated A, T, G, C.

The "Fab Four" DNA nucleotide bases - Chargaff noticed something odd: the amount of A always equalled the amount of T, and the amount of G always equalled the anount of C. This is Chargaff's Rule: A=T and G=C. (What's more, A+G = C+T -- and, of course, A+C = G+T).

- Even odder, different organisms turned out to have different DNA compositions. For instance: your DNA is almost exactly 40% G + C, while some bacteria have DNA that's over 70% G + C. Hmm. . .

Rosalind Franklin

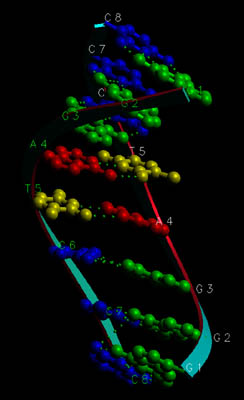

The famous "double helix". On the left, a still picture of a short piece of DNA. On the right, an animation of a rotating molecule (may not be viewable with all browsers).

- The sugars and phosphates of nucleotides link together to form the red-and-white spirals you can see. The bases (blue-and-white) fit in between the sugar-phosphate "backbones".

- A whole DNA molecule may consist of millions and millions of nucleotides.

- Here's a different picture. For clarity, the sugar-phosphate "backbone"

is drawn as a simple ribbonlike shape. You can see how the bases form "rungs"

linking the two sugar-phosphate chains together. The hydrogen bonds are

represented as rows of dots, and the whole thing looks like

a twisted ladder, or a spiral staircase:

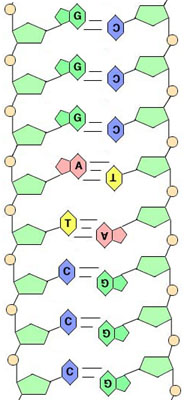

A short length of DNA - Let's "untwist" this helix for a moment. If you could do that, here's what

you'd see:

An "untwisted" short length of DNA- The sugars and phosphates are seen forming the sides of the "ladder."

- Hydrogen bonds between the bases hold the two strands of the helix together.

- Because of the shapes of the bases, however, A will only form hydrogen bonds with T, and G will only form hydrogen bonds with C. If one strand of a DNA helix has the base sequence, say, AAGCGAT, the other must be TTCGCTA, or the helix won't stay together. Now Chargaff's Rule makes sense!

- Because of complementarity, replicating DNA is fairly simple.

- The two strands of a DNA molecule are related to each other like a sculpture and its mold, or like a photo and its negative -- if you have one, you know exactly what the other one must be, and you can replicate one from the other.

- A DNA molecule "unzips" down the middle, breaking the hydrogen bonds.

- Free nucleotides are then fit onto each "unzipped" strand, and "welded" together into a new strand. Each old strand serves as a template for the new strand.