"The basic science is not physics or mathematics but biology--the study of

life. We must learn to think both logically and bio-logically." --Edward Abbey

I. Animalia -- Supplementary Web site:

Introduction to the

Animalia

- First, some basic definitions. . .

- Animals are multicellular -- made up of many cells

- Animals show cellular differentiation -- cells are specialized for various

functions

- Animals have no cell walls, but have cells held together by a meshwork

of fibers outside the cells themselves, called the extracellular matrix.

- The most common component of this mesh is a fibrous protein called collagen.

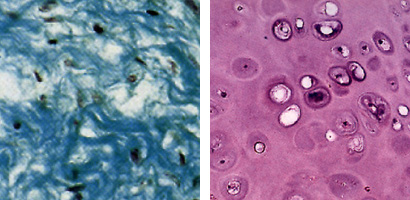

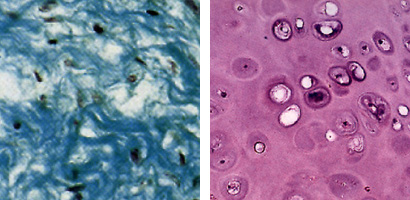

Left: Loose connective tissue from under the human face: the bluish fibrous

material is mostly collagen fibers.

Right: Cartilage tissue from the human nose: the actual cells are embedded in

pinkish-staining extracellular matrix.

- Animals are generally heterotrophic -- i.e. must feed on other organisms

- Animals are motile (able to move) at some point in their lives

- Animal organization

- Most animals have cells of the same type and function joined in

connected groups (often, but not always, in flat sheets). These groupings of cells

are tissues. There are four basic tissue types (not always present in all

animals):

- Epithelial -- tissue that lines cavities, often modified for secretion.

Examples: skin, linings of lungs, digestive tract

- Connective -- tissues usually used for structural support, with the cells

embedded in ECM. Examples: bone, cartilage, tendon, adipose (fatty) tissue, blood

- Nervous -- tissues used in transmitting signals. Example: brain tissue,

nerves

- Muscle -- tissues that contract and are used in motion.

- Several different types of tissue may be combined and work together to form

an organ. . .

- . . . and when several organs work together in a coordinated way, you have an organ

system.

- EXAMPLE: Cardiac muscle cells, joined together, form cardiac

muscle tissue. This tissue, plus some connective, epithelial, and nervous

tissue, make up an organ, the heart. The heart pumps blood through blood

vessels, and heart plus vessels collectively make up the circulatory system.

- Most people, when they hear the word "animal," think of a mammal. But animals

are far more diverse than that.

- Roughly one and a half million animal species are known to exist, with perhaps ten times

that many remaining to be discovered.

- Over half of all those animal species are insects.

- There are about thirty animal phyla (singular, phylum -- major

subdivision of a Kingdom). Unfortunately, we can only cover a handful in this course. . .

II. And now for a very quick look at a few of the major phyla (basic subdivisions

of the Kingdom Animalia):

- Porifera -- sponges

- No real tissues at all; a loose congregation of cells.

- There is often an internal skeleton of tough protein fibers (e.g. authentic

bath sponges) and/or hard, mineralized, needle-like pieces.

- Sponges feed by filtering water through specialized filtration chambers,

straining out food particles, and expelling the filtered water through a large pore.

- A few live in fresh water, but most live in the oceans.

- Cnidaria -- jellyfish, corals, sea anemones, etc.

- Cnidarians have true tissues -- an outer layer of cells and an inner layer

of cells -- but no real organs.

- There's some jelly -- called mesoglea -- in between.

- The body form is basically a sack. Food is taken in, and waste ejected,

through the opening of the sack, the mouth. Digestion happens in a saclike gut

(the gastrovascular cavity) inside the body.

- Most cnidarians capture prey with tentacles armed with specialized poison

stinging cells, the nematocysts. (These are what get you if you're stung by a

jellyfish!)

- Cnidarians show radial symmetry -- meaning that there are several

ways to divide them into mirror-image halves; there are no fixed left sides and

right sides.

- Most other animals are bilaterally symmetrical (meaning that they

have mirror-image left and right halves)

- We don't have time to cover the twenty-five bilaterian animal phyla (or

about twenty-five; there's some debate on how best to classify some of them).

What follows is a very brief overview of a few common animal phyla that you

might be familiar with:

- Phylum Nematoda: roundworms. Simple-looking worms, round in cross-

section and mostly microscopic -- but extremely important. There are tens of

thousands of species known, some of which are human parasites (intestinal

roundworms, hookworms, etc.), others of which parasitize animals (canine heartworm,

for example), and still others of which are economically important parasites of

plants that can cause major crop damage.

- Phylum Arthropoda:

by far the largest and most diverse phylum of all. Arthropods

have an exoskeleton (supporting structures that lies outside the body itself)

made up of chitin; the body is segmented, and the legs are also covered with

chitin and jointed so that they can move. Examples: Crustaceans (lobsters, crawfish,

shrimp, water fleas, etc.); arachnids (spiders, scorpions, ticks, daddy-longlegs, etc.);

insects (ants, bees, wasps, flies, true bugs, dragonflies, grasshoppers, etc. etc. etc.)

- Phylum Mollusca: soft unsegmented body with a single muscular foot, and a tissue flap around the body, the mantle, that often but not always secretes a hard calcium carbonate shell.

Examples: Snails and slugs; clams; squid and octopus; many others.

- Phylum Nematoda: commonly known as "roundworms" -- probably the second largest phylum. Unsegmented wormy body, round in cross-section. Most nematodes are

free-living, but many are parasitic. (Examples: heartworms, hookworms, Ascaris

the human intestinal roundworm, tomato root knot disease, etc.)

- The last phylum we'll mention is the Phylum Chordata -- which

happens to be the one in which you are classified. . . There are several subgroups

of the Chordata, but the best-known subgroup is the Vertebrata, the

animals with "backbones".