Symbiotic nitrogen fixation occurs in plants that harbor nitrogen-fixing bacteria within their tissues. The best-studied example is the association between legumes and bacteria in the genus Rhizobium.

Each of these is able to survive independently (soil nitrates must then be available to the legume), but life together is clearly beneficial to both. Only together can nitrogen fixation take place.A symbiotic relationship in which both partners benefits is called mutualism.

| Link to discussion of the role of nitrogen fixation in the nitrogen cycle. |

Rhizobia are gram-negative bacilli that live freely in the soil (especially where legumes have been grown). However, they cannot fix atmospheric nitrogen until they have invaded the roots of the appropriate legume.

The interaction between a particular strain of rhizobia and the "appropriate" legume is mediated by:

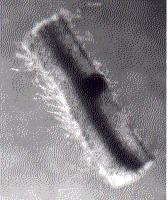

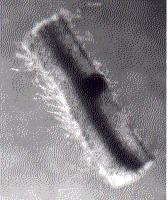

If the combination is correct, the bacteria enter an epithelial cell of the root; then migrate into the cortex. [Link to root structure.] Their path runs within an intracellular channel that grows through one cortex cell after another. This infection thread is constructed by the root cells, not the bacteria, and is formed only in response to the infection.

When the infection thread reaches a cell deep in the cortex, it bursts and the bacteria are engulfed by endocytosis into endosomes. At this time the cell goes through several rounds of mitosis — without cytokinesis — so the cell becomes polyploid.

The electron micrograph on the right (courtesy of Dr. D. C. Jordan) shows a rhizobia-filled infection thread growing into the cell (from the upper left to the lower right). Note how the wall of the infection thread is continuous with the wall of the cell. Once the thread ruptures, rhizobia are engulfed into endosomes within the cytoplasm (dark ovals).

Then the cell begins to divide rapidly forming a nodule. The stimulus for these changes is probably the secretion of cytokinins by the rhizobia.

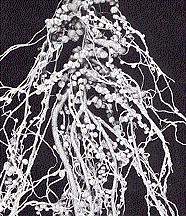

The photo on the left (courtesy of The Nitragin Co. Milwaukee, Wisconsin) shows nodules on the roots of the birdsfoot trefoil, a legume.

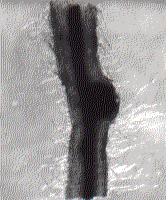

The rhizobia also go through a period of rapid multiplication within the nodule cells. Then they begin to change shape and lose their motility. The bacteroids, as they are now called, may almost fill the cell. Only now does nitrogen fixation begin.

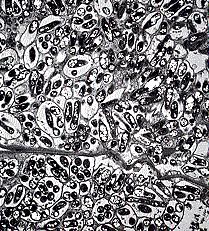

The electron micrograph on the right (courtesy of R. R. Hebert) shows bacteroid-filled cells from a soybean nodule. The horizontal line marks the walls between two adjacent nodule cells.

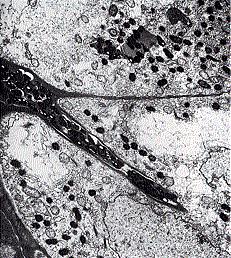

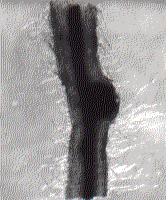

Root nodules are not simply structureless masses of cells. Each becomes connected by the xylem and phloem to the vascular system of the plant. The photo below on the left shows a developing lateral root on a pea root. On its right is a segment of a pea root showing a developing nodule 12 days after the root was infected with rhizobia. Both structures are connected to the nutrient transport system of the plant (dark area extending through the center of the root). (Photomicrographs courtesy of the late John G. Torrey.)

Thus the development of nodules, while dependent of rhizobia, is a well-coordinated developmental process of the plant.

|  |

Although some soil bacteria (e.g., Azotobacter) can fix nitrogen by themselves, rhizobia cannot. Clearly rhizobia and legumes are mutually dependent. What does each contribute to the process?

Isolated bacteroids contain all the metabolic machinery — including the enzyme nitrogenase — needed to fix nitrogen. Then why is the legume necessary? The legume is certainly helpful in that it supplies nutrients to the bacteroids with which they synthesize the large amounts of ATP needed to convert nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3)

The bacteroids need oxygen to make their ATP (by cellular respiration). However, nitrogenase is strongly inhibited by oxygen. Thus the bacteroids must walk a fine line between too much and too little oxygen. Their job is made easier by a second contribution from their host: hemoglobin.

Nodules are filled with hemoglobin. So much of it, in fact, that a freshly-cut nodule is red. The hemoglobin of the legume (called leghemoglobin), like the hemoglobin of vertebrates, probably supplies just the right concentration of oxygen to the bacteroids to satisfy their conflicting requirements.

Beyond these contributions, the plant must also, in ways as yet unknown, make possible the conversion of rhizobia that cannot fix nitrogen into bacteroids that can.

Because of the specificity of the interaction between the Nod factor and the receptor on the legume, some strains of rhizobia will infect only peas, some only clover, some only alfalfa, etc. The treating of legume seeds with the proper strain of rhizobia is a routine agricultural practice. (The Nitragin Company, that supplied one of the photos above specializes in producing rhizobial strains appropriate to each leguminous crop.)

How did two such organisms ever work out such an intimate and complex living relationship? Assuming that the ancestors of the rhizobia could carry out the entire process by themselves — as many other soil bacteria still do — they must have gained some real advantage from evolving to share the duties with the legume. Perhaps the environment provided by their host, e.g., lots of food and just the right amount of oxygen, enabled the rhizobia to do the job more efficiently than before.

| Welcome&Next Search |